When high school students in the West Hartford Public Schools district study World War II in the coming year, they will learn about more than just the typical hallmarks like Japanese American detention camps. They will also hear about Sadao Munemori, a soldier who died protecting comrades from a grenade. The 22-year-old posthumously became the first Japanese American awarded the Medal of Honor.

Lessons like this that delve beyond places have left teachers “humbled,” said Jessica Blitzer, the district’s social studies department supervisor who helped design curriculum for secondary grade levels.

“It's one of those moments where you think ‘How have we not been doing that?' These are moments where you realize this is really important, particularly given the population that we have in West Hartford, which is incredibly diverse in many ways," Blitzer said.

Three years after Connecticut became the third state to require Asian American and Pacific Islander history in K-12 education, a developed curriculum is being put into motion. For now, instruction is being rolled out in every grade except fourth and fifth. Most of the district's 9,300 students will have lessons integrated year-round. It will not be "the heritage month approach,” Blitzer said.

Since pandemic-fueled anti-Asian hate surged in 2020, Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander advocates have mobilized to make AAPI history mandatory learning through legislation or state education boards. Today, most AAPI adults want educators to teach history through the lens of racism, slavery and segregation, according to a 2024 survey. There have been some successes, with around a dozen states passing statutes requiring curriculum.

Beyond well-known events, classes are diving into topics like stereotypes of South Asians and Vietnamese refugees. But as efforts arise, so has disagreement among Asian Americans.

More progressive voices question the fairness and optics of seeking approval from lawmakers who have rejected history focused on other historically marginalized groups, such as expanded Black history curriculum that some critics more recently maligned as woke ideology or likened to critical race theory.

How teaching AAPI history finally came to the forefront

AAPI organizations devastated by reports of thousands of verbal and physical attacks, including the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings that left six Asian women dead, ramped up lobbying for more inclusive education. The hope was teaching about AAPI contributions would foster understanding. In July 2021, Illinois became the first state to mandate Asian American history. In 2022, New Jersey and Connecticut followed.

An expanded look at history includes reading accounts of new immigrants in San Francisco and Wong Kim Ark's Supreme Court fight for birthright citizenship. It also includes studying living figures like Chinese American architect Maya Lin.

Jason Oliver Chang, director of the University of Connecticut Asian and Asian American Studies Institute, helped develop legislation and train teachers. He remembers how lawmakers were moved by student testimonials.

“They were talking about their experiences sort of living two lives — one at school, one at home — feeling invisible and not feeling seen by their peers or respected by their peers,” Chang said. “Any time there’s a mention of someone that looks like them in a school curriculum, it's that they’re the bad guys.”

President Donald Trump has intensified scrutiny of how schools address race, threatening to withhold federal funds over diversity initiatives. The guidance has left some educators uncertain, despite some anti-DEI measures being blocked or put on hold by federal judges. Concerned teachers should stick to the framework and consult with colleagues, advises Kate Dias, president of the Connecticut's largest teachers' union.

“Almost every person who teaches content of this nature does not do it in a way to say, ‘Here’s all the injustices of the world,' ” Dias said. “The the call to action is ‘You need to now look at this information and you need to decide what it means.’ ”

Working with critics of race-conscious curriculum

Requiring AAPI history in schools has garnered bipartisan support. But in some conservative states, divisions have arisen over lawmakers who don't see systemic racism and social justice as essential to history.

When Florida adopted AAPI history legislation in 2023, critics saw it as hypocritical given the state denied Advanced Placement African American studies for being “critical race theory.”

In Arizona, failed legislation mandating AAPI and Native Hawaiian history lessons was endorsed by the Japanese American Citizens League. The Arizona chapter came out against it.

Chapter leaders asserted the bill's co-sponsor, state Republican Sen. John Kavanagh, and other supporters were only interested in rubber-stamping a sanitized history and ignoring African American and LGBTQ+ history.

Kavanagh equates talk of systemic racism with indoctrination. He previously supported barring college groups based on racial or ethnic identity and high school ethnic studies classes that seemed politicized.

He says teaching the history must be done in a “neutral, thorough manner.”

“I certainly have no problem teaching the history of Blacks or Hispanics or anybody,” Kavanagh said. “I don’t think there should be a course in a high school teaching students that this country is systemically racist when it’s not.”

The Arizona chapter of Make Us Visible, a national organization trying to establish AAPI history in every state, has faced criticism for not calling out right-leaning legislators. Astria Wong, chapter director, dismissed it.

“It’s really a good thing that even a conservative senator will support it. That means there is some bones in it," Wong said. “It should be bipartisan anyway.”

Amber Reed, co-executive director of AAPI New Jersey, finds it upsetting.

“What teacher wants to suddenly start teaching Asian American history while sort of being discouraged from teaching African American history or Latinx history, the history of all of our communities," Reed said.

A ‘deeper, richer’ look at American history

Before next summer, West Hartford Public Schools will assess how to improve curricula.

The goal is not to teach just “doom and gloom” to the student body — of which white children make up about 55%, Hispanics 21% and Asians and Black students more than 10% each — but a balanced look at history, said assistant superintendent Anne McKernan.

“There’s resistance, there’s perseverance, there’s greatness,” McKernan said. “As I look through the changes in elementary and the changes in secondary, it’s a richer look.”

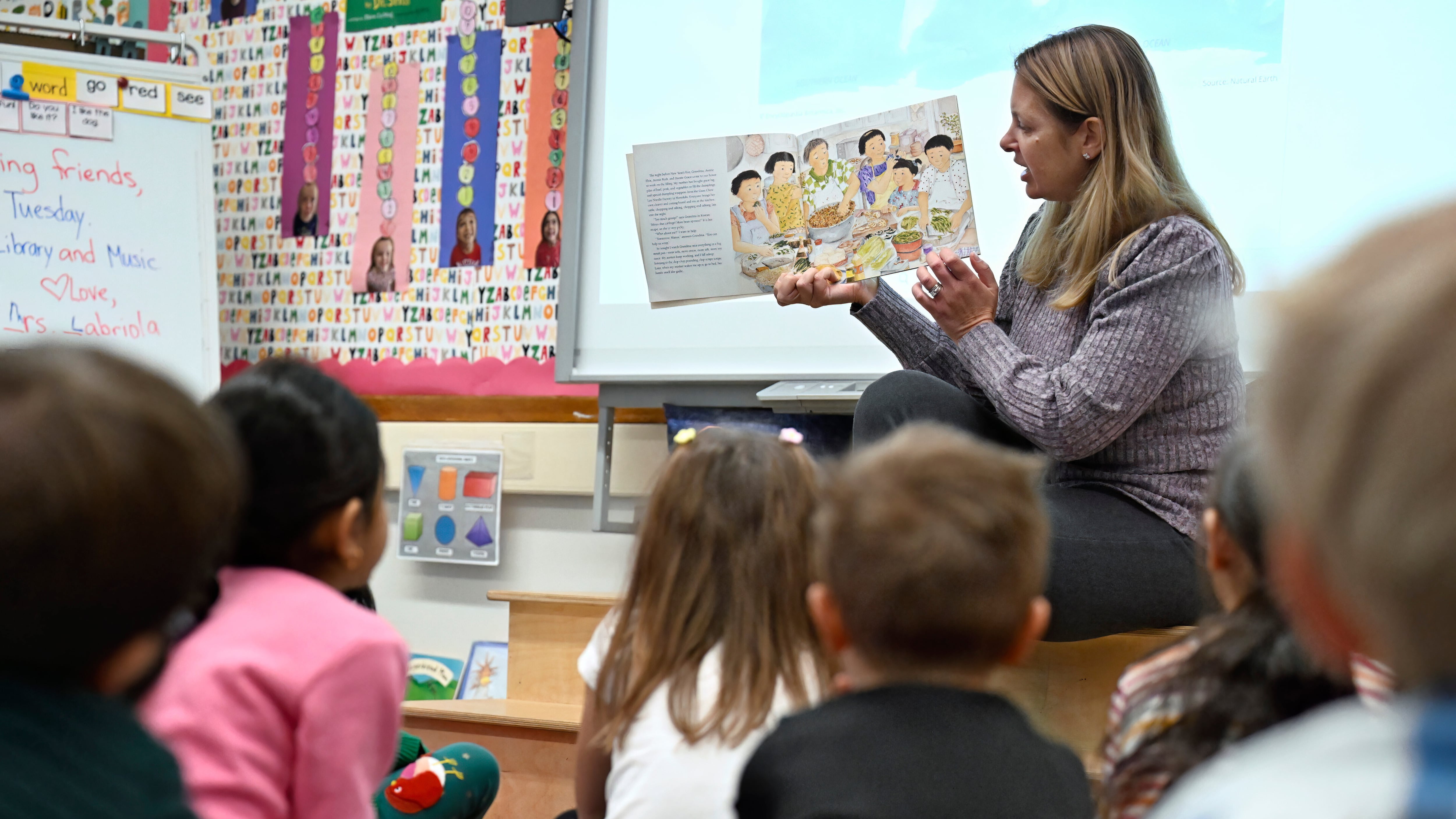

Elementary grades are using books to learn culture, reading comprehension and vocabulary, said Erika Hanusch, district literacy and social studies curriculum specialist. For example, kindergartners are reading the picture book “Dumpling Soup” by Jama Kim Rattigan. Centered around a family in Hawaii, the characters come from different Asian backgrounds.

“It’s really more so embedded through story and lens," Hanusch said. “And it’s giving teachers and students that natural opportunity to learn a little bit more about the where and the who and the traditions that come from those stories.”

___ Tang reported from Phoenix.

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.